The Benefits of Composting

When organic matter decomposes in landfills, it releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Composting allows microbes to break down organic matter, sequestering carbon and producing fertilizer.

Access Composting Resources from Drawdown Georgia

Market Readiness And Available Technology

While the technology for composting has not undergone significant changes, the industry is undergoing major changes in Georgia. With the creation of the Georgia Composting Council in 2024, Georgia became the 16th state to have a compost council approved by the US Composting Council.

CompostNow has also expanded its service in the metro Atlanta area and has received grant funding to offer free curbside pickup for compostables to 750 homes in Avondale Estates.

Composting as a Climate Solution in Georgia

The Drawdown Georgia research team estimates that our state could reduce emissions by one megaton (Mt) of CO2e by diverting 2 million tons of organic and food waste to composting.

Achievable Reduction Potential by 2030 / What Could We Achieve by 2030?

Achievable reduction potential is derived by taking the technical reduction potential, outlined below, and developing a more realistic forecast that considers current deployment rates, market constraints, and other barriers.

For composting, the Drawdown Georgia research team has calculated the achievable reduction potential to be 0.47 Mt of CO2e.

Technical Reduction Potential by 2030 / What Is the Upper Limit?

Technical reduction potential reflects the upper limit of emissions reductions for this solution without regard to the constraints that exist in the real world, such as economic or political considerations.

For composting, the Drawdown Georgia research team has calculated the technical reduction potential to be 1.38 Mt.

Current State of Landfill Methane in Georgia

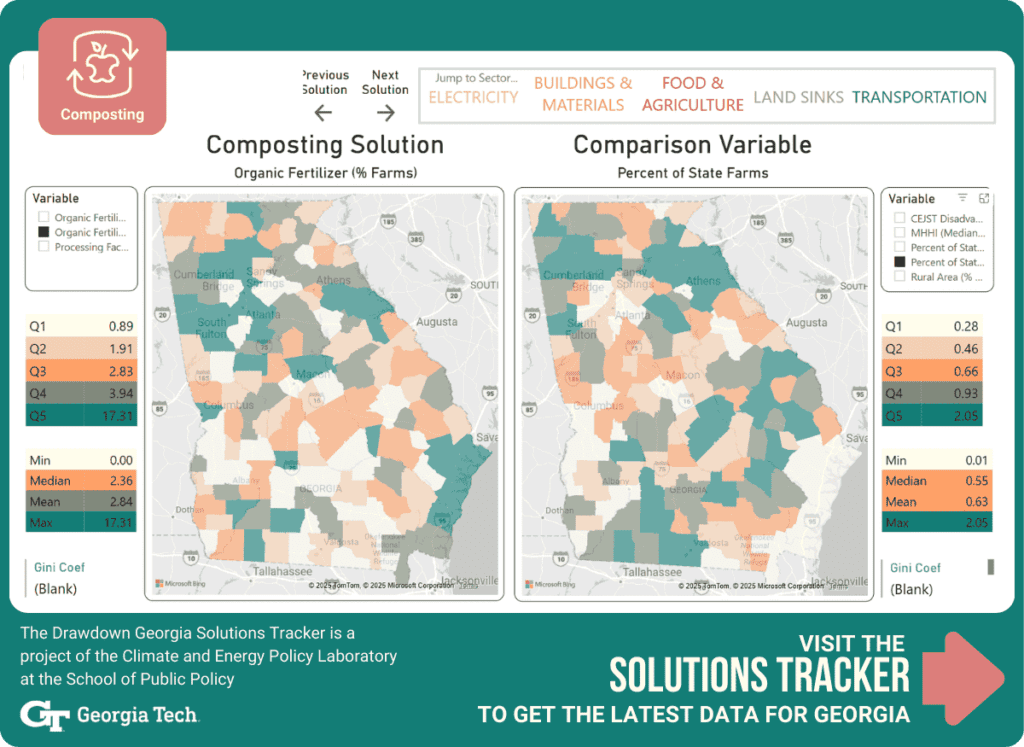

There is a small minority of farms that report using compost or other organic fertilizer options like manure to feed their crops. There are limited facilities where compost can be commercially processed, creating an opportunity to build this infrastructure with equity in mind. For example, CompostNow has partnered with Food Well Alliance to provide their finished compost to local BIPOC farmers in the metro Atlanta area.

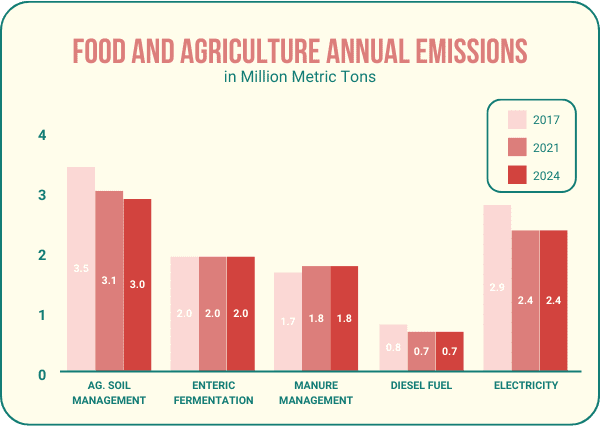

Changes to Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Food and Agriculture

Since 2017, the soil management emissions have decreased, while the manure management emissions remained relatively constant over the same time period. Because USDA only reports composting use data in a category that is shared with practices like using manure for fertilizer, both of these emissions sources are of interest.

Challenges in Scaling Composting as a Climate Solution

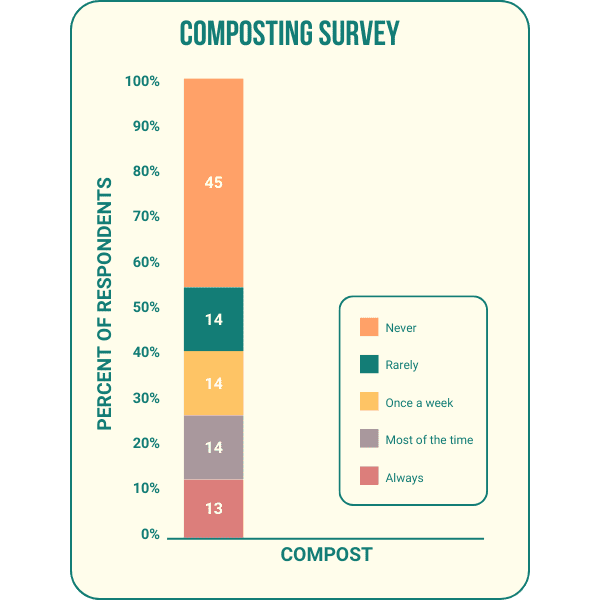

Composting had the lowest adoption rate among all the sustainable practices surveyed, according to a Georgia Tech/UGA survey of nearly 1,700 state residents. Nearly 45% of respondents reported that they never compost.

This suggests a lack of infrastructure, awareness, or convenience in implementing composting habits at home. While 13% "always" compost and 14% do so "most of the time," the overall low participation rate highlights an opportunity for educational campaigns, municipal composting programs, and incentives to make composting a more feasible and widely accepted practice.

How Reliable Is Our Estimate For This Drawdown Georgia Climate Solution?

Composting could reduce the number of landfills in Georgia, therefore reducing methane emissions. According to a study by the Georgia Department of Community Affairs, about 3 million tons per year of organic fractions of municipal solid waste is available for composting. The organic fractions do not include food waste but include mainly green waste such as paper, wood and yard trimmings.

Although some counties in Georgia operate composting facilities (for example, Clarke County), the majority of green waste is landfilled. The EPA estimated that about 0.16 t CO2e is reduced for every short ton of mixed organic waste. If 50% of organic waste generated in Georgia is composted every year, composting could reduce about 2.4 Mt CO2e by 2030.

Cost Competitiveness

Composting is one of the most cost-effective methods for lowering methane emissions from landfills. The composting process can be relatively low-tech and economical to implement. This is especially true at a municipal level, making it an accessible solution for many communities, although ongoing operating expenses can be high.

Beyond Carbon Attributes

This climate solution can enrich soil health, reduce methane emissions, and reduce the need for chemical fertilizers. Microbial activity degrades raw food wastes, resulting in end-products rich in microbial populations, creating extremely fertile soils. In addition, landfills would become smaller or potentially be eliminated. Approximately 25 million tons of municipal solid waste were recovered in 2018 through composting.

Composting can also provide increased food security, and composting at home is affordable. If compost is used to return nutrients back into exhausted soils on farmlands, the food waste loop can narrow, aiding in food security.

If operating costs for composting services were to become higher than those associated with landfills, this solution would have a negative economic impact. An example from Colorado found a backlash to mandatory composting when it added $4.45 to a household’s monthly expenses. Additionally, there are costs associated with the interventions and education required for households and businesses to change their disposal practices.

Data indicates that there is evident and significant inequality in the distribution of composting facilities in terms of population (GINI coefficient of 0.82). Six of the nine counties with a composting facility in Georgia are among Georgia’s wealthier counties. These counties include Cobb, Fulton, Dade, Fayette, Barrow, Butts, Clarke, Muscogee, and Chatham.

Most of these counties are near population centers, but Clarke and Barrow counties break this trend, likely because of their proximity to the agriculture-focused University of Georgia. This may also explain the relatively high adoption of organic fertilizer in the counties surrounding Clarke.